Decipherment commonly looks to ancient texts and carvings as its source of intelligent but unintelligible communication. These ancient languages such as the Egyptian Hieroglyphs and Kharoṣṭhī were forgotten and therefore unintelligible, until keys such as the Rosetta Stone were found which had the same information written in more than one text.

Our task will be more challenging since there will be no obvious key for the communication, yet a similar task to decipher the human genome has proven successful by finding keys in chemistry and the physical properties of biology. I hope that any civilization attempting communication across space would provide similar clues by using universal properties from mathematics and physics. This lab will explore the search for decipherment clues using a very simple encryption scheme.

One of the first popular methods for encoding information is attributed to Julius Caesar. His Caesar Cipher was used to encrypt messages to his generals in the field. While not a very secure method these days, few people were literate and fewer would have known how to attempt any cryptanalysis of his seemingly meaningless messages.

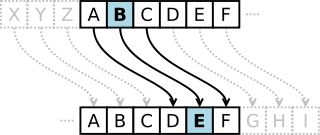

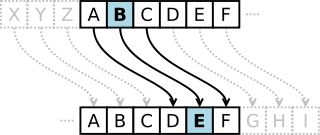

To perform encryption with a Caesar cipher, you first choose a number between 1 and 25, known as the rotation. Then for each letter in your plain-text message, replace it with the character that is found by adding the rotation to the position of the character. For instance, for a rotation of 4, the letter F would be translated into J, since F is the 6th letter in the alphabet and J is the 10th. If the position of the character plus the rotation is larger than 26 (the last letter Z), treat the alphabet as a loop and wrap around to the front. Decryption is performed in a similar manner, but instead the rotation is subtracted from the character to return us to the original plain-text message. This encryption process is illustrated below (thanks to Wikipedia); decryption follows the arrows in reverse.

Open a new python program called caesar.py. In this file, you will

first write two functions for encryption and decryption of strings.

encrypt(plain_text, rot) will take a string and an integer rotation between

0 and 25, (where 1 means A -> B, 2 means A -> C, etc) and return the rotated string.

decrypt(cipher_text, rot) will also take a string and an integer rotation

between 0 and 25 signifying the number of rotations backwards (where 1 means B -> A,

2 mean C -> A, etc), and return the reverse-rotated string.

You can test your functions using string="GREEN" and rot=13; your answer should be "TERRA". Also, any string encrypted with rot should decrypt back with the same rot, such that

decrypt(encrypt("TESTING", i), i)

should return "TESTING" for all feasible values of i.

Write a brute force function brute_decrypt(string) to print out all possible

Caesar rotations for a given string. Use this function to decrypt the following lines

of poetry (note: all four lines are encrypted with the same rotation).

WZDV EULOOLJ DQG WKH VOLWKB WRYHV GLG JBUH DQG JLPEOH LQ WKH ZDEH DOO PLPVB ZHUH WKH ERURJRYHV DQG WKH PRPH UDWKV RXWJUDEH

Open a file called Lab 9 Google Doc.

In this file, record the correct decryption and the rotation which was used.

Our first tool for analysis will examine the frequency of each letter in a standard text. While there are many different words and near infinite ways to combine them into sentences, there are regular patterns that we can observe across all words. The figure below (from Wikipedia) shows the relative frequency of each character, derived from counting the frequency of each character in a base text and then dividing by the total number of characters.

This information has been used to simplify early Linotype machines, which ordered the characters to be typed by their frequency (leading to the sometimes cryptic inclusion of etaoin shrdlu in newspaper articles).

Write a function in caesar.py called frequency_count(string).

This will return a list of relative frequencies for all letters A-Z found in the string.

Create a test string where you know the frequency of each character and make sure your

function returns the correct list of relative frequencies.

With 25 possible rotations, we can now examine the relative frequency count from each one and compare them to the base frequencies to find the best match. For this, we need one last tool, the Chi-square statistic, shown below.

Given two frequency distributions (O for Observed, E for Expected), the Chi-square statistic will tell us how good of a fit there is between these two distributions. Every observed frequency is compared to the expected frequency and squared, then divided by the expected frequency. These are summed to return the Chi-square statistic.

For our purposes, we do not need to compare this statistic to a table to see the probability of the match, we only need to find the rotation that produces the minimum Chi-square statistic (note that a perfect match will result in a statistic of 0, and any differences will result in a positive increase).

Write a function chi_square(observed_freq, expected_freq) in your

caesar.py to return the Chi-square statistic given the two frequency distributions.

This function should work as long as the two frequency distributions are the same length,

and also not be dependent on our specific use where the frequencies will be of length 26.

For example,

chi_square([0.3, 0.1, 0.6], [0.1, 0.2, 0.7])

should return 0.46428571428571419.

auto_decrypt(string, base_text) which takes an encrypted string and

the file name of a base reference text.

Your function will calculate the character frequencies for the encrypted string

and the reference text, then iteratively calculate the Chi-square statistic for

each possible reverse rotation.

Your function should print out the most likely rotation (minimum Chi-square statistic)

and decrypted message

along with the chi-squared statistic for that rotation.

Use Chapter 1 of Alice's Adventures In Wonderland as the base text to decrypt the three messages below.

V SBE BAR JRYPBZR BHE ARJ VAFRPG BIREYBEQF XRAG OEBPXZNA P DVBSK YHAOLY IL MPYZA PU H ZTHSS CPSSHNL PU NHBS AOHU ZLJVUK PU JVTTHUK PU YVTL QBSPBZ JHLZHY NDIXZ DI OCZ GJIB MPI ZQZMT KGVIZOVMT XDQDGDUVODJI RDGG WZ ZIYVIBZMZY WT DHKVXON AMJH NKVXZ ZQZMT NPMQDQDIB XDQDGDUVODJI DN JWGDBZY OJ WZXJHZ NKVXZAVMDIB IJO WZXVPNZ JA ZSKGJMVOJMT JM MJHVIODX UZVG WPO AJM OCZ HJNO KMVXODXVG MZVNJI DHVBDIVWGZ NOVTDIB VGDQZ DA JPM GJIB-OZMH NPMQDQVG DN VO NOVFZ RZ CVQZ V WVNDX MZNKJINDWDGDOT OJ JPM NKZXDZN OJ QZIOPMZ OJ JOCZM RJMGYN XVMG NVBVI

Report your results in Lab 9 Google Doc.

cs.centenary.edu through either Secure FTP or WinSCP using your

cs login and password.

Copy your caesar.py python file into the directory called lab9, along with any other

files you need to run your functions in caesar.py. Make sure

you have followed the Python Style Guide, and

have run your project through the Automated Style Checker.You must hand in: